We want to summarise and discuss our take on this very interesting paper. It is a recently published review of the research literature on guilt, shame and infant feeding ‘outcomes’.

The paper starts with the obligatory presentation and preservation of the sacred cow: breastfeeding has lots of health benefits for babies. We know and the authors know that the evidence for these claims is not straightforward, but we will park that issue for now. Alas, despite decades of a policy of promoting exclusive breastfeeding, the authors report that ‘compliance remains poor in developed countries’. They point to research thats shows correlations between stopping breastfeeding earlier and depression and anxiety. They consider whether women’s emotional state might affect for how long or how exclusively they breastfeed. They then propose that women’s emotional state might be a ‘modifiable factor’.

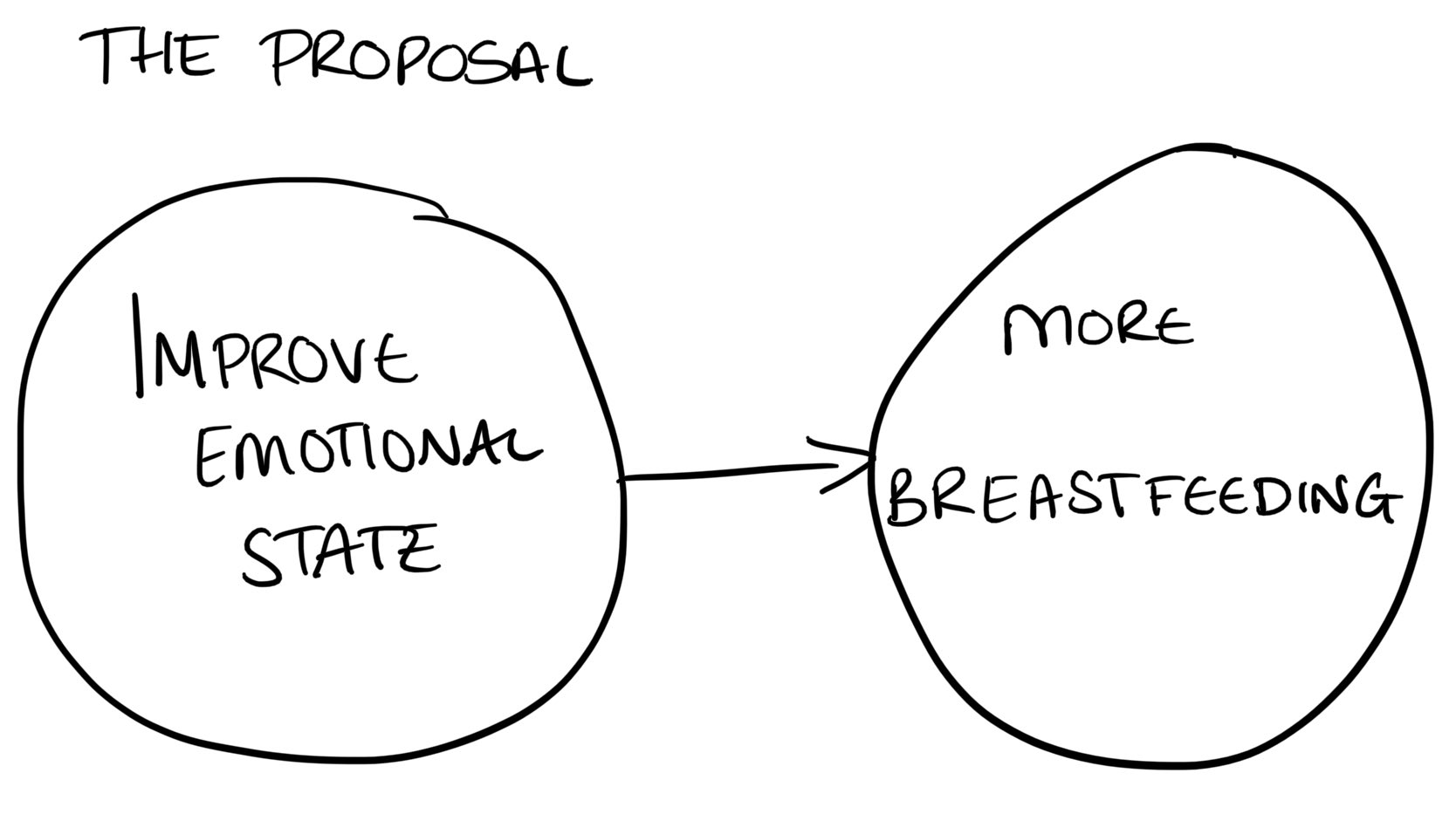

What is a modifiable factor? Basically, this is a factor that it might be possible to change to improve health outcomes. Essentially, they are suggesting that if we can improve women’s emotional state, they might breastfeed more (diagram ours):

But we feel this is over-simplified for several reasons. Deciding to stop breastfeeding, or to mixed feed rather than exclusively breastfeed, can be an important part of caring for our emotional wellbeing or of looking after ourselves if we are going through mental illness. Breastfeeding problems can cause emotional distress and contribute to a worsening of mental health, or even the development of mental illnesses for some people. Emotional distress and mental illness could make the demands of breastfeeding more taxing. We argue that the relationship between emotional state and whether or not someone initiates breastfeeding, stops breastfeeding or introduces formula is not straightforward. It could go in either direction and be affected by many factors.

The authors go on to point to guilt and shame as ‘outcomes’ of infant feeding. They define guilt as a perceived ‘moral transgression’ and shame as the perception of ‘failing in front of others’. They review the literature on:

- guilt and shame in relation to infant feeding ‘outcomes’ and

- how guilt and shame are experienced differently by mothers using different feeding methods.

They use a thorough approach to identifying and reviewing the relevant literature. We won’t go into the details of this, but suffice to say we recognise the work and diligence that has gone into the review and we are grateful to have the data summarised in one paper in this way.

So what did they find?

In three quantitative studies and one mixed method study, they found:

- more guilt in women who combination feed compared to those who exclusively breastfeed

- more guilt in women who intended to breastfeed but ended up formula feeding, compared to those who intended to formula feed

- more guilt in women who formula feed compared to those who breastfeed

- that guilt is more pronounced when antenatal feeding intentions were different from how the baby was actually fed.

In six studies of breastfeeding mothers, they identified two themes:

- Underprepared and ineffectively supported

- Morality and perceived judgement

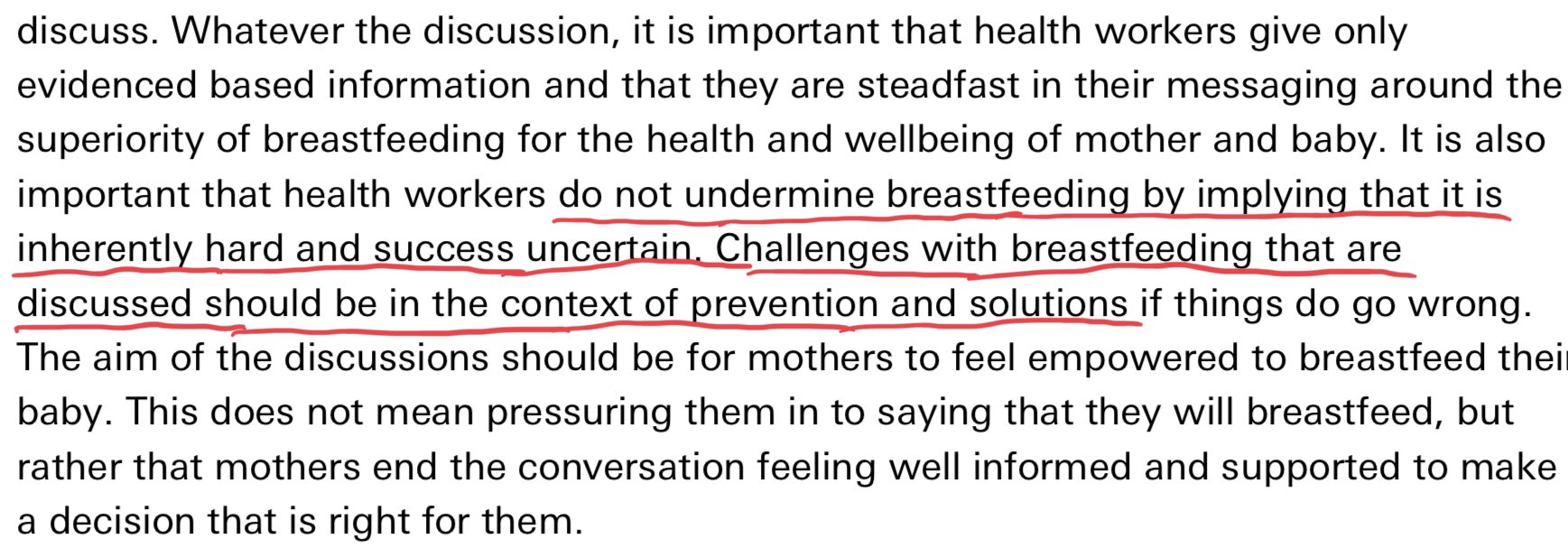

Let’s discuss the first theme, ‘Underprepared and ineffectively supported’. Women felt that healthcare providers did not prepare them for breastfeeding challenges and that reality was at odds with antenatal expectations. *Cough cough*. Take a look at this policy currently in place in all UK maternity services:

The authors write that breastfeeding challenges led to self-doubt and anxiety and undermined breastfeeding ‘self-efficacy’ (i.e. women’s confidence in their ability to breastfeed.) But we are sceptical about framing this as a confidence issue. Perhaps women are simply recognising that their difficulties render breastfeeding unsustainable?

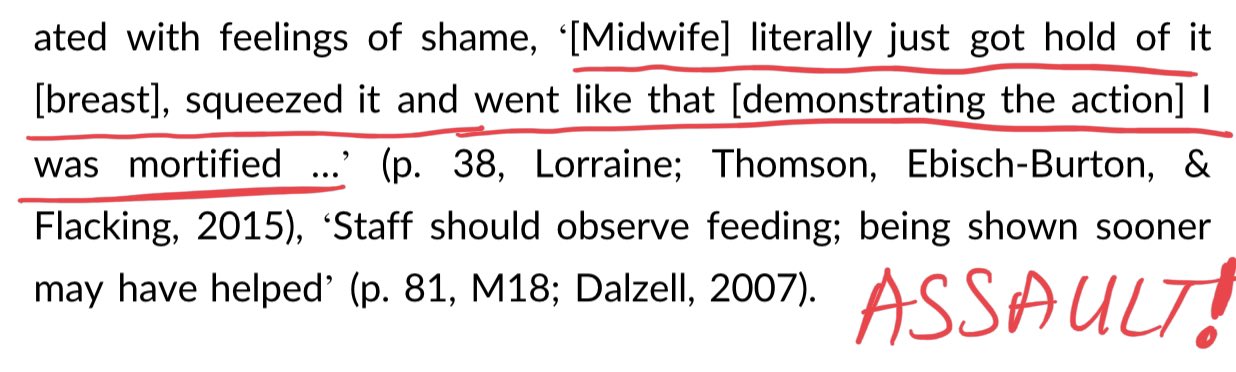

Women also felt shame in response to over-involved care and non-consensual breast handling or grabbing by healthcare professionals. We would call manhandling breasts or touching them without consent assault.

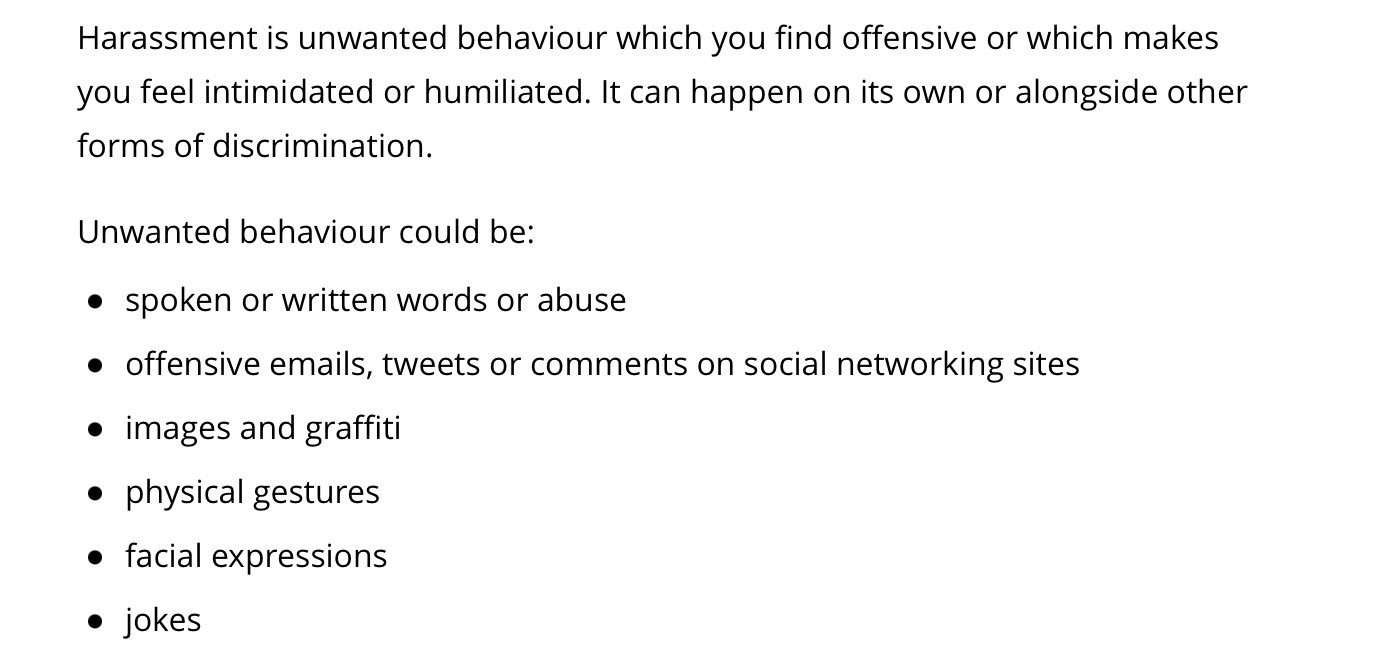

Women also reported critical comments from healthcare professionals about theirs or their baby’s ‘shortcomings’ (e.g. being told their breasts or nipples were too big or small). Unfortunately we relate. Some of us were told our babies were too ‘lazy’ to breastfeed. Blaming newborns for their breastfeeding difficulties… What do we call that? We propose that communicating in such insulting and degrading ways constitutes harassment. Here is the legal definition from the Citizen’s Advice Bureau:

Now let’s look at the second of the themes the authors identified, ‘Morality and perceived judgement’. Women reported feeling compelled to adhere to ‘breast is best’ discourse and seeing formula feeding as ‘wrongful’. Formula feeding was seen as an indication of inadequate mothering and women who breastfed were seen as better mothers. Perceived judgement was associated with self-blame. Mothers reported feigning effortless breastfeeding experiences to escape judgement from healthcare professionals or family members. This also contributed to some women not seeking help from healthcare professionals or support from other mothers for fear of being judged. Some were concerned about breastfeeding in public in case people thought it should be done behind closed doors.

The authors also identified nine studies that looked at the experiences of mothers who formula fed. They found two themes here:

- Frustration with infant feeding care

- Failures, fears and forbidden practices

We’ll start with the first theme, ‘Frustration with infant feeding’ care. Women were frustrated and confused by inconsistent advice about feeding. Healthcare professionals were quick to blame (or should we say, quick to shame) mothers for breastfeeding difficulties. Interestingly, the research literature calls women’s feelings of being undermined, publicly embarrassed and like they have done something wrong ‘guilt’.

Women reported healthcare professionals making them feel guilty (i.e. shaming them) by asking if they were still breastfeeding. As a result, some women concealed that they were formula feeding from healthcare professionals. Which leads us to the second theme, ‘Failures, fears and forbidden practice’. Women felt like failures if they were not breastfeeding. This was associated with self-blame. The research suggested that guilt and shame could come from external sources as well as internal feelings. However, nobody seems to have stopped to ask: from where have women internalised the idea that formula feeding is bad or that breastfeeding difficulties are their fault and something to be ashamed of? It is remarkable that this question is not being asked, since breastfeeding problems and decisions to stop breastfeeding are not unusual.

Interestingly, although the literature review searched for the term ‘stigma’, none of the reviewed papers discuss it. But they did identify women fearing judgement, getting the impression that formula feeding was forbidden or even being made to feel like they were criminals for formula feeding.

Consider these statements in the light of current policy, which says maternity services cannot:

- Demonstrate safe formula preparation in groups where women might be intending to breastfeed

- Have information about formula on public display or in public leaflet stands

- Show any images of bottles or teats.

If you act like something is a dirty little secret, is it such a surprise that people feel a lot of shame for doing it?

The authors suggest that guilt and shame might contribute to poor ‘breastfeeding outcomes’, but what is a breastfeeding outcome? Is the method the marker of success? Why aren’t we looking at whether babies’ nutritional needs are being met (i.e. they are not losing excess weight or experiencing faltering growth). Or infection rates? Or actual health outcomes related to infant feeding? Why aren’t we looking at whether parents feel feeding is sustaining their family life and is not a source of excessive stress?

The authors propose that there should be more honesty with parents about breastfeeding difficulties. They suggest that strategies should be given to enhance breastfeeding confidence and extend breastfeeding duration. But, there are some problems with this:

- Honesty about breastfeeding problems is not compliant with current policy (see above)

- A recent NICE evidence review failed to find any evidence for what might prevent or resolve breastfeeding problems. So what strategies should be given?

- What makes the authors think that breastfeeding difficulties or decisions to mixed feed or stop breastfeeding are confidence issues?

- Should the goal be to extend breastfeeding duration? Just give us the unvarnished truth in the form of frank, evidence-based information that facilitates informed autonomous decisions.

If you provide information in a manner designed to manipulate peoples’ behaviour, you destroy trust. Healthcare providers need to trust us to make good decisions for our families. That means we need to know that breastfeeding problems are common and we need realistic expectations about what can be done about them. (And while we are on the subject of presenting information accurately, can we return to the sacred cow and ask that it be replaced with a realistic estimation of the absolute benefits and risks of all feeding methods, with frank acknowledgement of the limits of the current evidence!)

The authors discuss over-involved care and non-consensual breast touching and suggest this results from midwives acting as ‘technical experts’ rather than ‘skilled companions’. We don’t want companions! We want evidence-based healthcare for our infant feeding problems. And we need to be safe from assault and harassment from healthcare professionals, or anyone else providing healthcare support with infant feeding.

The authors suggest resource constraints and work environments are the barriers to midwives acting as ‘skilled companions’. There is not a single mention of the absence of any good evidence for midwives (or anyone else) to draw on to help families to prevent or resolve breastfeeding problems. We would point to the one exception to this: there is good evidence that early formula supplementation prevents excessive weight loss and the need for phototherapy for neonatal jaundice in breastfed babies. We should be told that too so we can make informed decisions!

The authors suggest that future research should look at the relationship between shame and guilt and infant feeding ‘outcomes’. We propose that we scrutinise current policy and root out half truths, misleading statements and anything that causes guilt or shame for families. They suggest that while it is important to promote breastfeeding, people who formula feed should get information on how to do it safely. We ask: is it important to promote breastfeeding? Our bodies, our decisions! Can we just have information that respects our autonomy, rather than trying to steer us down a particular path?

The authors propose that the ‘all or nothing’ breastfeeding mentality be changed to a more incremental ‘every feed counts’ approach to breastfeeding support. We think this is a terrible idea and, to be honest, are a bit disappointed that the authors went so far as to recommend this without consulting families.

Why do we think this is a terrible idea?

- What does the evidence say about how much breastfeeding is needed to achieve a meaningful health benefit? (isn’t the goal here public health outcomes, not changing women’s behaviour?)

- We feel this approach would create huge pressure. Are women with breastfeeding problems to be encouraged to persist with ‘just one more’ miserable, painful, distressing breastfeed because ‘every feed counts’?

- What effect would such an approach have on someone expressing for hours every day for a very small volume of milk?

We think this paper presents an excellent outline of some aspects of women’s experiences of infant feeding care. It exposes a policy and practice that is coercive to its core – shame is not a bug here, it is a feature. But ‘every feed counts’ doesn’t change this. It is proposing doing the same old thing but trying to be a bit nicer about it.

We think the time for small, incremental change is over. We need to take breastfeeding off centre stage and put families on it where they belong. We need infant feeding policies and practices that serve us and our needs, not that demand us to sacrifice ourselves in the name of a decades-old public health agenda that has yet to demonstrate a single improvement in public health outcomes in the UK or any other high income setting. This seems a long way off, since professionals and researchers in this field are still clinging on to the old. So, parents, we are going to have to take the reins back!

How should we do it? Here’s what we propose: We tackle shame head on. We speak out fearlessly about the worst, most shame-filled, darkest aspects of our infant feeding experiences and we back each other up. We will no longer live in shame. We will make sure that no mother ever thinks she’s the only one.

And we make the research and policies and all the contradictions and absurdities therein visible. Why? Because infant feeding policy is institutional gaslighting par excellence. It is time to take a long hard look at what is going on. We are inspired by this recent article by Ramani Durvasula that identifies institutional gaslighting. It is time to turn off the gaslights. It is time to trust ourselves and insist on the compassionate, autonomy-promoting, safe infant feeding care we all need and deserve.

This is an edited version of a commentary first published as a thread on Twitter.